A British show provided inspiration for an American TV classic.

Norman Lear and Bud Yorkin had a knack for adapting British sitcom formats and spinning ratings gold in America. In 1971, their Tandem Productions scored a culture-shaking hit with All in the Family on CBS. A year later, they launched another hit on NBC. Like Family, it had a British origin and a hilariously irritable (and frequently bigoted) main character. Sanford and Son would become a major hit, anchoring an entire night that was once considered TV’s Death Valley. Here’s how a blue comedian, a sharp team of Black actors, and music legend Quincy Jones all figured into the making of a classic series.

When Lear and Yorkin formed Tandem in 1958, they made film projects as well as variety specials and series for television. In 1971, Tandem launched All in the Family at CBS. Developed by Lear and Yorkin based on the long-running British BBC1 series Till Death Do Us Part, Family framed itself in middle of ongoing cultural discourse. With the openly bigoted, ultra-conservative Archie Bunker pitted against his hippie daughter and son-in-law with his long-suffering wife stuck in the middle, the show became a huge hit based on its ability to generate laughs while tackling frequently taboo subjects. Realizing the British format/American social issue formula was a winner, Tandem threw a twist on it for their next project.

Steptoe and Son was a British Series that had two distinct runs in the 1960s and 1970s for a total of eight series (or seasons, in the U.S.). Like Till Death Do Us Part, the show orbited around the culture and generational clash of its two leads: in this case, an outrageous junkman father and his kinder son. Lear and Yorkin developed the new show based on Steptoe together, but Lear was uncredited. When NBC picked up the new series, Yorkin ran it so that Lear could focus on their CBS stable. All in the Family would generate the spin-off Maude in 1972, and continue to build out with shows like Good Times and The Jeffersons. Yorkin’s focus could then stay on their new NBC show, Sanford and Son.

For the stars, the producers recruited Redd Foxx and Demond Wilson. Foxx, born John Elroy Sanford, was a successful stand-up comedian, known for his “blue” (profane) material. He had released a string of well-liked comedy albums and crossed over from predominantly Black venues to playing in front of white audiences. Wilson was a veteran of both Vietnam and Broadway, and had made his way into film and television. Foxx was cast as Fred Sanford (they named the character after Foxx’s brother), a junkyard and salvage business proprietor. Wilson played his long-suffering son, Lamont.

The much-loved theme for the series was composed by music legend Quincy Jones. Properly called “Sanford and Son Theme (The Streetbeater),” the tune made its way onto both Jones’s 1973 album You’ve Got It Bad Girl and his greatest hits collection. It also landed on the Post’s list of the 50 greatest live-action TV themes songs of all time.

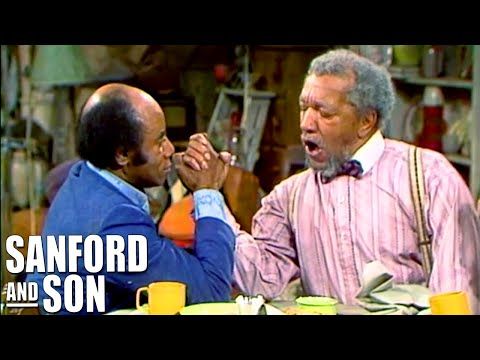

In terms of the series, like Family, much of the fun of Sanford and Son came from the fabulously cranky Fred playing against other characters. He and Lamont would battle over social issues, frequently resulting in him berating his son with “you big dummy.” Other frequent foils were Ethel (Beah Richards) and Esther (LaWanda Page), the sisters of Fred’s late wife, Elizabeth; Fred’s friend Grady (Whitman Mayo); neighbor Julio (Gregory Sierra); and Lamont’s friends Rollo (Nathaniel Taylor) and Ah Chew (Noriyuki “Pat” Morita). Fred would usually shower visitors in a barrage of insults, but suffer comeuppance when his various get-rich-quick schemes would fall apart. He would frequently try to salvage a moment by pretending to have a heart attack, invariably accompanied by cries of, “It’s the big one, Elizabeth! I’m comin’ to join you, honey!”

Though it was saddled with what was seen as the “death slot,” 8 p.m. on Friday nights, Foxx’s outrageousness and the likeability of the rest of the cast drove the show to #6 in the ratings in its first short season. A short but generally positive review from The Hollywood Reporter in 1972 praised Foxx and Wilson’s inherent charisma. When season two kicked off in September of 1972, it was the #2 show in all of television, behind only All in the Family. The show’s success broke the stranglehold that ABC’s The Brady Bunch had on the night and allowed NBC to build a formidable line-up behind Sanford. By the 1974-1975 season, Sanford led a Friday night block that included Chico and The Man, The Rockford Files, and Police Woman, all of which were in the Top 15. During that season, the show was again #2, just fractions of viewership behind Family.

Despite the success, things weren’t perfect behind the scenes. Toward the end of season three, Foxx walked off the show amid a battle with Tandem over salary and show profits. Fred was said to be visiting family out of town. Foxx would be absent for six season three episodes and three in season four. Tandem sued Foxx, but eventually a new deal was worked out. Foxx was given a raise, giving him the same salary that Carroll O’Connor was earning for Family ($25,000 per episode), as well as 25 percent of Tandem’s net profits on the show.

During the sixth season, the show began to slip in the ratings. A spin-off, Grady, had already come and gone. Sensing an opportunity to gain a huge asset while eliminating a threat, ABC made Foxx a major offer. Along with a significant bump in salary, Foxx would have his own variety series, The Redd Foxx Comedy Hour. Foxx took the offer, and Sanford and Son folded. NBC tried to continue with a spin-off, Sanford Arms, but Wilson left in his own salary dispute; though a number of other actors continued with the new show, it only ran for four episodes. NBC attempted a reboot called Sanford in 1980; the son was dropped because Wilson declined to return. Sanford ran for 26 episodes before cancellation.

Sanford and Son remains a much-loved series. While it was important to NBC for breakthrough successes on Friday nights, it was a trailblazer for Black-led sitcoms, debuting as it did before other big Tandem successes, like Good Times, The Jeffersons and Diff’rent Strokes. Like Archie Bunker, Foxx’s Fred Sanford didn’t have to be right, or even likeable, to be funny, and that was liberating for all of the performers around him. Foxx’s style of comedy has echoed down the decades in blustery father figures without number, and the series remains well-regarded by critics and fans alike. It might have been set in a junkyard, but Sanford and Son was a TV treasure.